Strong Bones for Life

The link between Lean Muscle Mass and Bone Density for Women.

The Connection Between Lean Muscle Mass and Stronger Bones in Women: A Deep Dive into the Science

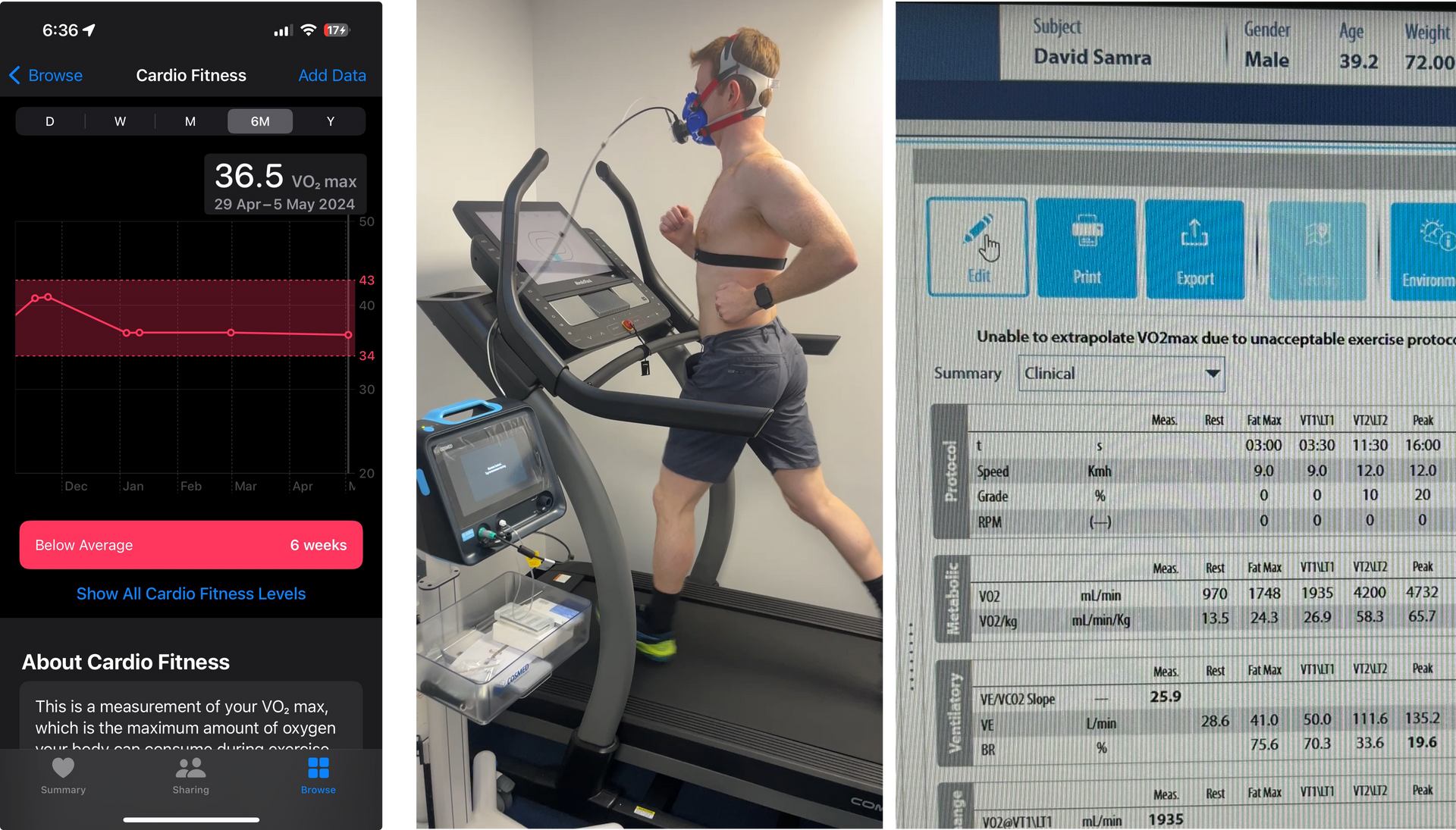

Bone health is a critical issue for women, particularly postmenopausal women who face a heightened risk of osteoporosis and fractures. Strong bones are the foundation for an active, independent lifestyle, yet they often receive less attention than other health priorities. One of the most effective and scientifically backed ways to support bone health is through building lean muscle mass.

This blog will dive into the scientific research underpinning the relationship between lean muscle and bone health, with a focus on women. We’ll explore how targeted exercise, particularly under the guidance of an Accredited Exercise Physiologist (AEP) Cameron Hyde, can empower women to strengthen both their muscles and their bones.

The Science Behind Muscle and Bone Health in Women

1. Muscle-Bone Crosstalk

Muscle and bone tissues are interconnected through a phenomenon known as

mechanical loading. When muscles contract during exercise, they exert stress on bones, signalling them to adapt by increasing bone density. Recent research highlights a bidirectional communication between these tissues via chemical messengers called myokines and osteokines. These signalling molecules promote the maintenance and growth of both muscle and bone.

- Scientific Evidence: A 2020 review in Endocrine Reviews emphasizes the role of muscle contractions in stimulating bone-building cells (osteoblasts), a process particularly effective in weight-bearing and resistance exercises.

2. Hormonal Changes and Bone Loss in Women

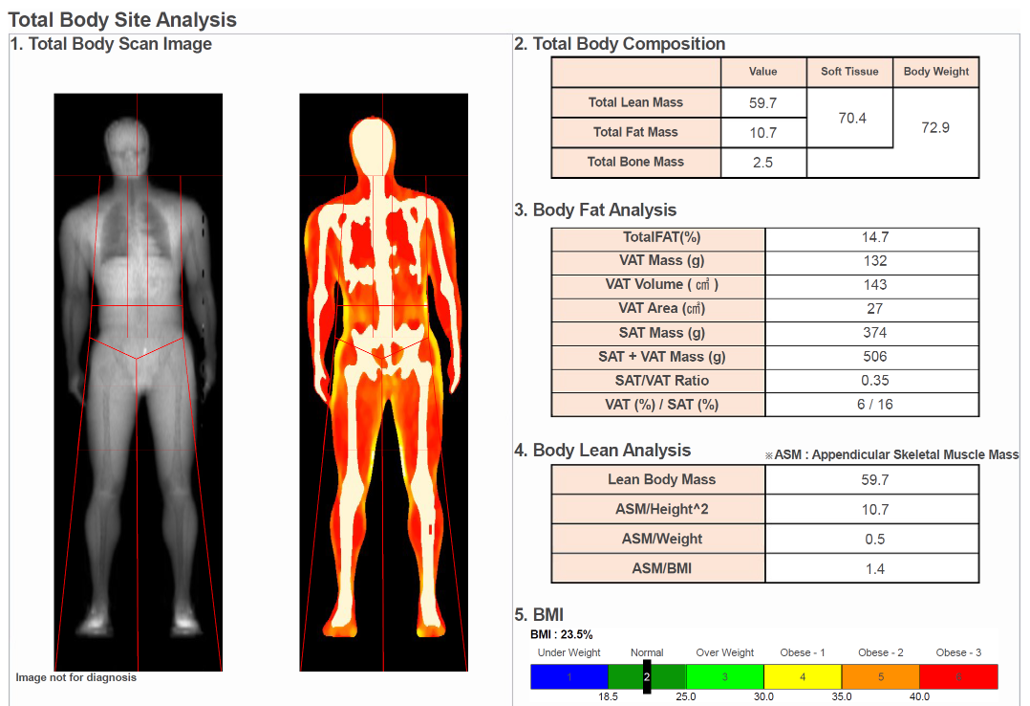

Women experience a rapid decline in bone density post-menopause due to decreased estrogen levels, which play a protective role in bone remodelling. This hormonal shift also affects muscle mass, increasing the risk of

sarcopenia (age-related muscle loss). Building lean muscle mass can counteract these changes by enhancing the forces acting on bones and slowing bone loss.

- Scientific Evidence: A 2019 study in Osteoporosis International showed that women with higher muscle mass experienced slower rates of bone loss, especially in weight-bearing bones like the spine and hips.

3. Site-Specific Bone Benefits

Research indicates that exercises targeting lean muscle growth can improve bone density at specific sites most vulnerable to fractures, such as the hip and spine.

- Scientific Evidence: The LIFTMOR (Lifting Intervention for Training Muscle and Osteoporosis Rehabilitation) trial, led by Professor Belinda Beck, demonstrated that high-intensity resistance training significantly improved bone density and strength in postmenopausal women. This study also highlighted safety and efficacy, with proper supervision being key to avoiding injury.

Why Lean Muscle Mass Is Essential for Women’s Bone Health

1. Improved Bone Mineral Density (BMD)

Lean muscle mass exerts greater mechanical stress on bones, stimulating bone remodeling and increasing bone mineral density. For women, this is especially critical as BMD naturally declines with age.

- Scientific Insight: A 2018 meta-analysis in Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise found that resistance training effectively increases BMD in postmenopausal women, reducing the risk of osteoporosis-related fractures.

2. Protection Against Osteoporosis

Osteoporosis affects an estimated

1 in 3 women over 50, making it a significant health concern. Regular resistance training and lean muscle maintenance have been shown to mitigate this risk.

- Scientific Insight: A study in The Journal of Bone and Mineral Research revealed that higher levels of muscle mass are strongly correlated with greater bone strength and lower fracture rates in aging women.

3. Reduced Fall and Fracture Risk

Strong muscles improve balance, coordination, and stability, reducing the likelihood of falls—a leading cause of fractures in older women.

- Scientific Insight: A 2017 review in The Journal of Gerontology showed that strength training programs focusing on lower-body and core muscles significantly decreased fall rates in older women by improving functional mobility.

Exercise Recommendations for Women to Build Muscle and Strengthen Bones

Not all exercise is equally effective in enhancing muscle and bone health. Women benefit most from a combination of high-impact activities and resistance training, tailored to individual needs and abilities.

- Resistance Training

- What it does: Builds lean muscle, increases mechanical load on bones, and improves overall strength.

- Examples: Goblet squat, Rack Pull, Deadlift. These need to be Heavy!

- High-Impact Exercises

- What it does: Provides direct mechanical stress to bones, stimulating bone formation.

- Examples: Jumping, skipping, and running.

- Balance and Core Work

- What it does: Enhances stability, reducing fall risk and improving functional strength.

- Examples: Yoga, pilates, or stability exercises like single-leg stands.

- Supervised Programs for Safety and Efficacy

Women, especially those with osteoporosis or at risk of fractures, should work with qualified professionals to ensure safe progression. Our experienced exercise physiologist Cameron Hyde can design an evidence-based, individualized program to maximize results while minimizing injury risk.

How an Accredited Exercise Physiologist Can Help

An Accredited Exercise Physiologist (AEP) has specialized knowledge of exercise prescription for health and chronic conditions, including osteoporosis. Working with Cameron Hyde ensures:

- Tailored Plans: Programs are customized to your fitness level, bone health status, and personal goals.

- Evidence-Based Guidance: Incorporating the latest scientific research into your training regimen.

- Safety First: Proper technique, progression, and monitoring to avoid injury.

Cameron’s expertise in high-intensity resistance training for bone health aligns with findings from studies like the LIFTMOR trial, ensuring optimal benefits for women.

Practical Takeaways for Women

- Start Strength Training: Include resistance exercises targeting major muscle groups 2–3 times per week with 1 day in between each session.

- Incorporate Impact: Add activities like jumping or hopping to your routine if medically appropriate.

- Prioritize Consistency: Bone and muscle adaptation take time, so regular exercise is key.

- Work with a Professional: Seek guidance from our expert EP Cameron Hyde to ensure your exercise routine is both safe and effective.

Final Thoughts

The link between lean muscle mass and stronger bones is well-established in scientific research, particularly for women. Building muscle not only improves bone density but also reduces the risk of falls, fractures, and osteoporosis, ensuring long-term health and independence.

Empower yourself with the tools to strengthen your bones and muscles. With evidence-based guidance from an experienced exercise physiologist, you can take control of your bone health and thrive at any age.

For personalized support, contact Cameron Hyde, AEP, and start your journey toward stronger bones today. Your future self will thank you!

References

- Muscle-Bone Crosstalk and Mechanical Loading

- Hamrick, M. W. (2010). A role for myokines in muscle-bone interactions. BoneKEy Reports, 7, 102. doi:10.1038/bonekey.2010.55.

- Zoladz, J. A., & Majerczak, J. (2016). Insights into muscle-bone crosstalk: Exercise as a powerful stimulus for bone health. Bone, 84, 14–22. doi:10.1016/j.bone.2015.12.015.

- Hormonal Changes and Bone Loss in Women

- Greendale, G. A., Sowers, M., & Han, W. (2012). Bone loss over the menopause transition: A systematic review of bone turnover markers. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research, 27(1), 56–64. doi:10.1002/jbmr.534.

- Wong, S. K., Chin, K. Y., & Ima-Nirwana, S. (2019). Osteoporosis and sarcopenia: The bidirectional relationship. Clinical Interventions in Aging, 14, 633–649. doi:10.2147/CIA.S202472.

- High-Impact and Resistance Training Benefits

- Beck, B. R., Daly, R. M., Singh, M. A. F., & Taaffe, D. R. (2014). Exercise and sports science Australia's position statement on exercise prescription for the prevention and management of osteoporosis. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 17(4), 291–296. doi:10.1016/j.jsams.2013.11.003.

- Watson, S. L., Weeks, B. K., Weis, L. J., Harding, A. T., Horan, S. A., & Beck, B. R. (2018). High-intensity resistance and impact training improves bone mineral density and physical function in postmenopausal women with low bone mass: The LIFTMOR randomized controlled trial. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research, 33(2), 211–220. doi:10.1002/jbmr.3284.

- Site-Specific Bone Benefits

- Kemmler, W., & von Stengel, S. (2011). Exercise and osteoporosis-related fractures: Perspectives and recommendations of the EFAB (Expert Forum on Exercise and Bone). Osteoporosis International, 22(11), 2769–2784. doi:10.1007/s00198-011-1760-5.

- Nichols, D. L., Sanborn, C. F., & Essery, E. V. (2007). Bone density and young athletic women: An update. Sports Medicine, 37(11), 1001–1014. doi:10.2165/00007256-200737110-00006.

- Muscle Mass and Reduced Fracture Risk

- Scott, D., Blizzard, L., Fell, J., & Jones, G. (2010). A prospective study of the associations between muscle mass, muscle strength, and muscle power with incident fractures in community-dwelling older adults. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research, 25(4), 858–866. doi:10.1359/jbmr.091020.

- Schafer, A. L., & Schwartz, A. V. (2021). Association of sarcopenia with bone health and fracture risk. Current Osteoporosis Reports, 19(1), 62–69. doi:10.1007/s11914-021-00693-7.

- Fall Risk Reduction Through Exercise

- Sherrington, C., Fairhall, N., Wallbank, G., Tiedemann, A., Michaleff, Z. A., Howard, K., & Lord, S. R. (2019). Exercise for preventing falls in older people living in the community: An abridged Cochrane systematic review. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 53(17), 905–911. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2019-100732.

- Resistance Training for Bone Density Improvement

- Zhao, R., & Xu, Z. (2012). The influence of exercise on bone mass and bone strength: A meta-analysis. PLOS ONE, 7(12), e50377. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0050377.

- Marques, E. A., Mota, J., & Carvalho, J. (2012). Exercise effects on bone mineral density in older adults: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Ageing Research Reviews, 11(2), 217–225. doi:10.1016/j.arr.2011.11.003.